Visiting the Berlin Film Festival for the first time involved a slew of remarkable highlights, not the least of which was the sheer number of world-class filmmakers, writers and actors in attendance.

Visiting the Berlin Film Festival for the first time involved a slew of remarkable highlights, not the least of which was the sheer number of world-class filmmakers, writers and actors in attendance.

But beyond this, and beyond the vast plethora of films available for viewing, most for the first time anywhere in the world, and beyond the star-studded parties and functions, something else struck me, something which in a way was more significant than anything else – and that was the sheer importance given to the act of film-viewing and the elevation of cinema as an art form in the city. Much has been written about cinema as a space of semi-religious devotion but attending films in Berlin gives a profound substance to the metaphor. For, unlike the very wonderful Durban International Film Festival, in which Durban’s cinephiles are given the rare chance to access a cross-section of global film, there was no sense at Berlin that the festival was catering to a minority or a subculture.

Instead the entire city seemed to come alive. Evidence of the Berlinale was everywhere, compounded and enhanced by the massive corporate sponsorship by companies such as L’oréal and BMW. Wherever I went, visitors to the festival were carrying festival bags and wearing their accreditation badges. But it was in the actual cinema spaces that the sacred nature of film was given the most credence. Without wandering too much into the arena of pretentiousness, there was a palpable sense of reverence from the audiences. Not a single cell phone went off in any of the screenings I attended, and while the Berlin public was visibly excited that the city was hosting big name actors such as Matt Damon, Jude Law, Anne Hathaway and Hugh Jackman, the most veneration was granted not to those who occupy the pages of the planet’s tabloid publications, but to those who, although often invisible and relegated to the role of service providers by the global film industry, are at the very core of cinema – the directors.

And so, while by Durban standards, it seemed a little like overkill, there was something very moving about watching Jane Campion, director of such masterpieces as The Piano and Portrait of a Lady, being given such a prolonged and heartfelt applause for merely entering the cinema. The response she received went way beyond any notion of star-worship. While the audience’s reaction was certainly an acknowledgement that someone deservedly famous was in their midst, the overriding sense was one of graciousness and thanks for what she has given us.

Campion was at the festival for the theatrical screening of her brilliant six-part television series Top of the Lake, part of a recognition by the festival of the increasing artistic importance of television in recent years. Later, Campion, together with Gerard Lee, with whom she wrote Top of the Lake – and also her breakthrough film Sweetie – spoke at the Berlinale Talent Campus to a room packed with young filmmakers eager to glean some pearls of directorial wisdom. Hosted by film historian Peter Cowie, Campion talked casually about her ascent from someone who really had no idea what she wanted to do with her life to her position today as one of the world’s most well-loved filmmakers. Like many in her profession, she started off studying at art school, gradually finding her way into the medium that has come to define her. And, like many of the directors that spoke at the festival – and also those who speak at the Durban International Film Festival – Campion was remarkably humble, revealing the vision of a director to be something that is continually evolving and also the product of the talents with whom she has been fortunate enough to collaborate, giving actor Harvey Keitel with whom she worked in The Piano a particularly loud shout-out.

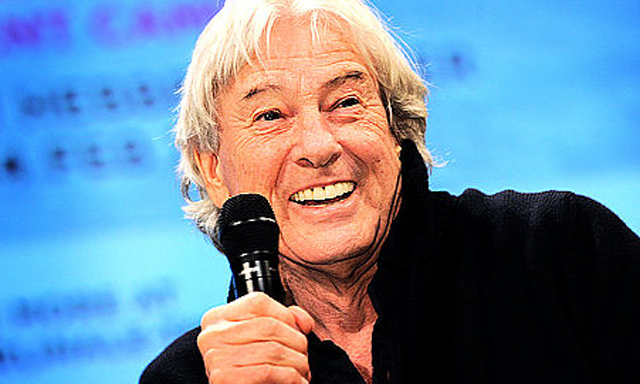

Earlier in the week, I had been fortunate enough to listen to master-director Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct, Starship Troopers) discuss his career, which, like Campion’s, hadn’t been premised on any particularly strong youthful vision of filmmaking, but was instead something he simply fell into, having started his career making promotional videos for the Dutch marines as part of his military service. I learned how Verhoeven’s starting point in any movie is fine art, and it was fascinating to hear him talk about how the brutal editing techniques used in Robocop were modelled on the brusque modernism of Mondrian’s paintings, and how his use of lighting in the pastel-noire of Basic Instinct was inspired by the works of David Hockney.

Earlier in the week, I had been fortunate enough to listen to master-director Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct, Starship Troopers) discuss his career, which, like Campion’s, hadn’t been premised on any particularly strong youthful vision of filmmaking, but was instead something he simply fell into, having started his career making promotional videos for the Dutch marines as part of his military service. I learned how Verhoeven’s starting point in any movie is fine art, and it was fascinating to hear him talk about how the brutal editing techniques used in Robocop were modelled on the brusque modernism of Mondrian’s paintings, and how his use of lighting in the pastel-noire of Basic Instinct was inspired by the works of David Hockney.

These were just some of the inspiring public conversations held by some of the world’s greatest filmmakers. I also had the privilege of listening to Shortbus‘s John Cameron Mitchell discuss the use of sex as a cinematic language, and to our own Oliver Hermanus talking, together with American filmmaker David Gordon Green, about writing emotion onto screen. So engaging were these conversations that I found myself struggling to tear myself away to watch the incredible array of films available at Berlin. Yet sometimes too much of a good thing is absolutely fine. If you’re an aspiring director or writer, or simply just a dedicated lover of film, I can’t recommend a visit to the Berlinale highly enough. For me, it was the experience of a lifetime, and one I plan on repeating next year, and every year after that.

These were just some of the inspiring public conversations held by some of the world’s greatest filmmakers. I also had the privilege of listening to Shortbus‘s John Cameron Mitchell discuss the use of sex as a cinematic language, and to our own Oliver Hermanus talking, together with American filmmaker David Gordon Green, about writing emotion onto screen. So engaging were these conversations that I found myself struggling to tear myself away to watch the incredible array of films available at Berlin. Yet sometimes too much of a good thing is absolutely fine. If you’re an aspiring director or writer, or simply just a dedicated lover of film, I can’t recommend a visit to the Berlinale highly enough. For me, it was the experience of a lifetime, and one I plan on repeating next year, and every year after that.

Images courtesy of Talent Campus Berlin